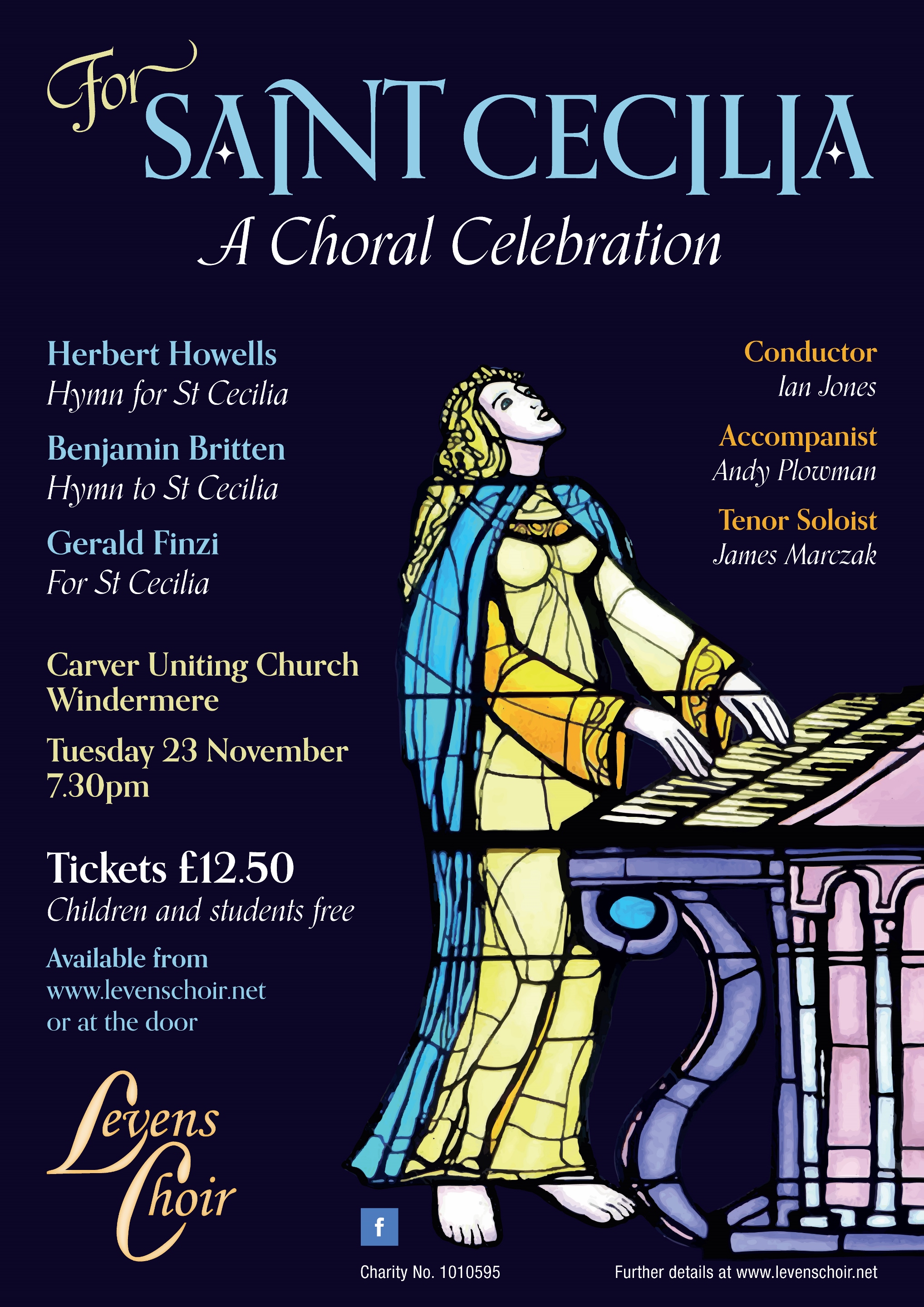

A Winter's Journey - Kirkby Lonsdale

Christmas and Summer Concerts afford directors the opportunity to programme shorter works from the repertoire and to juxtapose pieces separated by time, location and genre. This year’s A Winter’s Journey Christmas Concert, staged in the beautiful setting of St Mary’s Church, Kirkby Lonsdale and presented by the highly renowned Levens Choir, was a veritable smorgasbord of delightful a cappella pieces spanning seven centuries and from as many countries. The thoughtful and informative programme notes provided translations and texts as well as detailed background notes. This is by no means de rigueur for concert goers but here it enabled the audience to engage meaningfully with each piece and to empathise with the sentiments being expressed by the choir. This was much appreciated.

The Choir’s Musical Director, Gawain Glenton, explained that the programme comprised pieces centred on the theme of Epiphany, the time in the Christian Year after Christmas when the church celebrates the journey made by the Magi in search of the newly-born Christ Child. Glenton’s own championing of Early Music was evident in the programming and in his clever and thoughtful separation of vocal forces as befitting the music. His direction is clear and assured and he enjoys an obvious rapport with his singers.

It should be said that there is nothing more challenging for a choir than to sing unaccompanied polyphonic music especially in other than their native tongue and when split into up to eight parts. If tuning slips, or an entry is missed, there is nowhere to hide! Whilst there was the odd rushed entry and occasional lapses in tuning, the choir handled the demands of the music admirably. Vocal lines were clearly enunciated and sibilants (a personal grouch) underplayed and controlled. It would be true to say that whilst not sonorously impacting, the singers looked less at ease with the demands of the earlier pieces in the programme than with those that concluded it. Here there were smiles to match the greater freedom in body language and increased focus on the conductor than on the music. Every performer wants to get it right, but it is important to look as though you are enjoying the challenge!

Highlights from the first half were the opening rendition of Orlando de Lasso’s Omnes de Saba for double choir. The balance across the eight parts was excellent and the tuning and diction very secure. This flowed with a good deal of energy and joy. I was impressed with the confidence shown by the choir whilst performing Clemens non Papa’s Magi Veniunt Ab Oriente. The voices were separated either side of the audience but strong leads in each section ensured a confident rendition even if the tuning suffered a little at times.

Rebecca Dale’s Stopping By Woods set familiar words to challenging melodic lines and adventurous harmonic progressions. Both ends of the choral spectrum were particularly impressive with clear and strong top soprano notes and resonant bass roots. There was also a lovely, clear soprano solo line evident in some of the textures.

The second half began with a lower voices only setting by Lodovico da Viadana of Tria Sunt Munera from the west end of the church which was then answered by an upper voices rendition of David Willcock’s How Far Is It To Bethlehem? from the chancel steps (not literally!) Will Todd’s My Lord Has Come is undoubtedly one of the best and hardest pieces to have entered the repertoire in recent years and there was a real commitment shown in trying to realise its dynamic and textural demands.

The programme was now on more familiar ground as it concluded with some seasonal favourites. Particular praise should go to the excellent soloist in Cornelius’ much loved The Three Kings: the solo every baritone covets singing but fears being given!

And so the journey ended and the weary travellers turned homeward. Whether the Wise Men or the indefatigable members of Levens Choir, each and everyone deserves much praise for their endeavours and best wishes for a joyful Christmas and Happy New Year.

Duncan Lloyd 14/12/2025

Christmas Concert - Silverdale

On an unseasonably warm evening we were treated to a festive box of choral goodies from the Levens Choir under the direction of Gawain Glenton who took us on a musical “Winter’s Journey” for Advent from the Renaissance to the present day.

The choir was on excellent form, their confidence growing as the concert progressed. The opening pieces by Lassus and Palestrina were restrained but the singers were well into their stride for Joanna Marsh’s In Winter’s House, coping extremely well with its challenging harmonies. It’s clear too that the choir has worked hard on diction.

Concluding the first half, the choir moved into a semi-circle formation, so effective for the gorgeous polyphony of the Clemens non Papa Magi veniunt ab oriente. This and Rebecca Dale’s evocative setting of Robert Frost’s Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, were particular highlights.

The second half was a mix of traditional carols and Renaissance motets. I enjoyed the dynamics and phrasing in Chilcott’s Shepherd’s Carol, Todd’s My Lord Has Come and Hopkins’ We Three Kings. Here the choir were on familiar territory, making the most of the beautiful acoustic at St John’s. Again, every word was audible. The choir should also be congratulated on their blend – no individual voice(s) could be heard.

Maybe the choir could have looked a little more joyful in conveying the Christmas story, which might in turn have counteracted the slight drop in pitch in a couple of pieces. And the full gusto of the traditional carols resulted in the odd over-zealous descant. But which choir isn’t tempted to give their all in these familiar pieces!

Heather Willes

50th Anniversary concert

.png) The Levens Choir held their 50th Anniversary Concert at the Carver Uniting Church in Windermere, and it was a glorious event. A substantial and enthusiastic audience heard a wide variety of composers from Monteverdi to Elgar to Tippett.

The Levens Choir held their 50th Anniversary Concert at the Carver Uniting Church in Windermere, and it was a glorious event. A substantial and enthusiastic audience heard a wide variety of composers from Monteverdi to Elgar to Tippett.

The choir, its large complement of singers ranged into an arc, split the evening into two sections. During the first, they celebrated their strong connection to local landscapes and communities, through Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Arthur Somerville, the latter born in Windermere. The choir’s voices soared during these vocal miniatures with inflexions of renaissance madrigals, as soloists were wowing the audience with their pitch perfect musical lines soaring above their fellow female and male choristers.

Of special note were the three modern partsongs of the Penrith-born Philip Cooke. His composition to the words of A.E. Houseman, How clear, how lovely, was particularly beautiful, and the lilting voices of the choir gave it particular poignancy.

The second half of the concert was devoted to the favourite musical moments of the choir members sung in preceding years. Their choices ranged from the17th century of Italy to the late 20th century of Britain, showcasing their incredible range and versatility. Particularly memorable were Monteverdi’s Cantate Domino, along with O Clap Your Hands by Orlando Gibbons, Tippett’s Steal Away, alongside the unjustly neglected Imogen Holst’s A Hymn to Christ and finally Crossing the Bar by Rani Arbo, which showed off the choir’s vocal precision and innate musicality. It was a perfect way to finish.

The choir was led by its inspirational Music Director, Gawain Glenton. While at the helm these past three years, he has inspired the singers of the choir to perform an ever expanding repertoire of music. This was amply demonstrated and more in the concert. Ian Jones, the founder and long term director of the choir, also conducted a lovely cameo of Valiant for Truth by Vaughan Williams with the choir.

Russell Zubrinich

50th Anniversary Concert

.png) This was the first of two concerts to celebrate the Choir’s 50th anniversary. The concert was in two halves: the first had a Cumbrian feel, with works by local composers or commissioned for local events.

This was the first of two concerts to celebrate the Choir’s 50th anniversary. The concert was in two halves: the first had a Cumbrian feel, with works by local composers or commissioned for local events.

Beginning with Elgar’s My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land, the choir gave us warm harmonies with a strong melody and smooth, precise dynamics. Then Vaughan Williams’ short and lively Over Hill, Over Dale was a charmingly light contrast before Elgar’s Weary Wind of the West took us back to reflection before building to a grand crescendo.

Self’s settings of two poems by Christine Cochrane, a late and much-missed member of the choir, began with Harpa Poetica, a hymn to the Welsh harp, an evocative interpretation of this lovely instrument for voices, with male and female sections of the choir complementing each other perfectly. This was followed by Thoughts of a Corncrake - a complete contrast - delightfully comedic and sung with great precision and enjoyment.

The local composer Arthur Somervell was next in the programme, with three quite different songs: the poignant Once I was Young, followed by the melancholy No Longer Mourn and the ebullient Ah! My Sweet Sweeting, a delightful love-lilt. A contrasting trio together forming a coherent whole and delivered with aplomb.

The contemporary local composer, Phillip Cooke, provided the next three songs; I Stood on a Tower, by Tennyson, with close, dissonant harmonies - a very reflective song, very difficult to sing and very well sung. Green, the next piece, was much lighter with a sparkling top A from a solo soprano the highlight. The cycle closed with How Clear, How Lovely with text from Housman and gentle harmonies to conclude the trio of songs and the first half of the concert.

The theme of the second half was ‘favourites’ - songs members of the choir, past, present and those no longer with us had enjoyed over the 50 years. We began with two Renaissance motets: Monteverdi’s Cantate Domino, with perfect harmonies and lively dynamics, then Tallis’ Salvator Mundi, showing the choir’s skill in handing the text from section to section. Two pieces from Orlando Gibbons - The Silver Swan, a short, melancholy madrigal, contrasted with O Clap Your Hands, from Psalm 47, a joyous rendition, full of lively dynamics. The balance of this choir is really outstanding.

Lotti’s Cruxifixus led into Vaughan Williams’ Valliant for Truth, conducted by Ian Jones, the founder and long-time music director of the Choir, whose presence was warmly appreciated by all. Then Tippett’s Steal Away - the Afro-American spiritual given a reflective but joyous rendition - followed by Imogen Holst’s A Hymn to Christ, the lovely harmonies a fitting tribute to John Donne’s words of love and hope. Chilcott’s The Isle is Full of Noises was a lively, fun impression of Caliban’s imaginings before Arbo’s setting of Tennyson’s Crossing the Bar concluded the concert.

Thanks to everyone involved in the organisation at St Oswald’s and, of course, to Gawain Glenton, his splendid choir and everyone associated with making the event run so smoothly.

SP 11July 2025

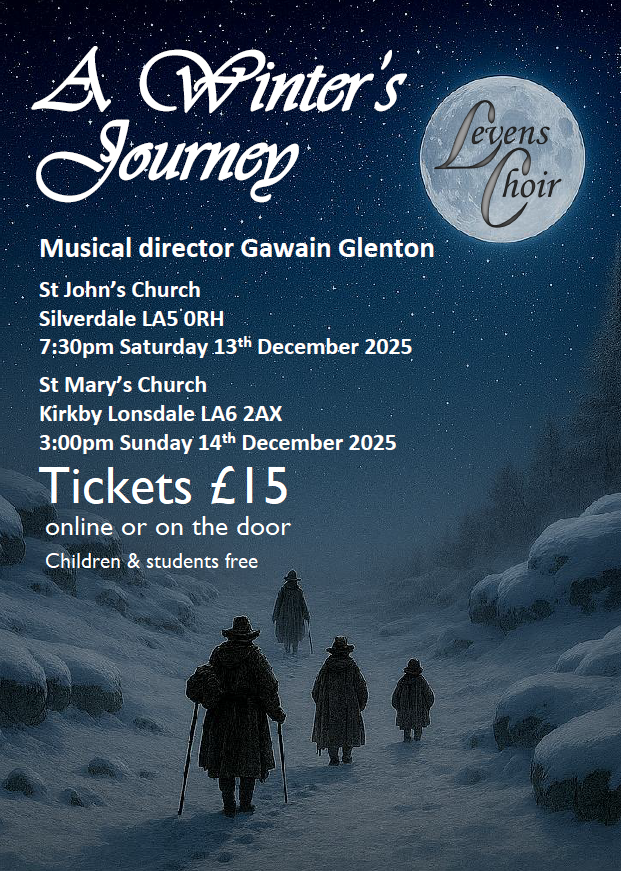

Lancaster concert

The concert began with Herbert Howell’s Hymn for St Cecilia. Composed to words by Ursula Vaughan Williams, the widow of Ralph, this work gave the Levens Choir the opportunity to set out their stall and demonstrate what they are capable of. They delivered a performance rich in tonal colour and musical shape. The syncopated and layered vocal entries at the beginning of verse two were a particular highlight.

The concert began with Herbert Howell’s Hymn for St Cecilia. Composed to words by Ursula Vaughan Williams, the widow of Ralph, this work gave the Levens Choir the opportunity to set out their stall and demonstrate what they are capable of. They delivered a performance rich in tonal colour and musical shape. The syncopated and layered vocal entries at the beginning of verse two were a particular highlight.

This was followed by Maurice Duruflé’s four unaccompanied motets. Each motet has a very different sound and feel, and the choir skilfully navigated the light and shade piece by piece. The first two motets rely on their contrapuntal texture to drive the music forward. The choir rose to the challenge, and the opening of ‘Tota pulchra es’ really shone; well done to the upper voices!

It would be tempting for a choir to find their niche with Howells and the Duruflé motets and stick with works from a similar oeuvre. Instead Levens Choir took the more challenging and risky choice to expand their repertoire with the next item of the programme: Cecilia McDowall’s Aurea Luce. With close, sometimes mildly dissonant harmonies and spiky staccato phrases, this work was a great contrast to the previous musical items, enhancing all of them and underscoring the talents of the Levens Choir and the excellent programming of their Musical Director, Gawain Glenton. The choir was supported by sensitive yet assured playing by organist Ian Pattinson.

Gabriel Fauré’s Cantique de Jean Racine was the next item in the programme. The opening of this work was another example of the fine quality of performance on offer; from the organ’s flowing arpeggiated figures, we then had each vocal part entering in a staggered manner, beginning with basses and tenors before moving onto the altos and finally sopranos. Diction was clear, entries confident, and the vocal blend between parts was seamless. Fauré’s chorale-like writing contrasted nicely with McDowall’s Aurea Luce.

The first half closed with Arvo Pärt’s Beatitudes. Another lovely contrast in style, showcasing the many strengths of the choir. This is an incredibly challenging work, with a mixture of large melodic leaps and close harmony writing. The choir were able to draw out the light and shade of the piece, and the atmosphere, emotion, and execution of the work more generally was a brilliant way to bring the first half to a close.

With such varied repertoire, programmed so thoughtfully, the audience would have surely been content with the concert ending there. However, these works were only the appetiser. The second half was dedicated to Duruflé’s Requiem. The audience witnessed a masterful display from organist Ian Pattinson. At times subtle, supportive, and balanced perfectly with the choir; at others, displaying an expert command of all the organ has to offer to elevate the music to another level. The gradual build in the second part of the ‘Kyrie’ was evidence of this. Sublime playing!

‘Domine Jesu Christe’ provided an opportunity for sections of the choir, including individuals, to really shine, and Rebecca Chandler’s performance in ‘Pie Jesu’ was delivered with sensitivity and a rich tone which was expressive and skilfully shaped across her vocal range.

By the time the choir closed the concert with ‘In Paradisum’, it had become art reflecting reality. The serene vocal lines washing over the organ’s long pedal notes were the perfect end to the performance. What a treat for the audience!

Phil Allcock

Kendal Concert

Anyone who thinks they don’t like choral music should have been dragged along to this excellent concert. At times thrilling, often moving and always engaging, it was a feast of varied delights. It was all performed with great conviction by a choir on top form.

Anyone who thinks they don’t like choral music should have been dragged along to this excellent concert. At times thrilling, often moving and always engaging, it was a feast of varied delights. It was all performed with great conviction by a choir on top form.

The choir perhaps took a minute to get fully into their stride in the opening piece, ‘A Hymn for St. Cecilia’ by Howells. We then moved on to four motets by Duruflé. Not many choirs are as confident as Levens in unaccompanied singing, particularly in music as harmonically complex as this. There was some lovely quiet singing and beautifully controlled dynamics without any harshness making the most of the fine acoustic of St. George’s church. ‘Aurea Luce’ by Cecilia McDowall was well blended and the challenging entries, harmonies and counterpoint were navigated with ease.

We travelled almost 150 years back in time for the ‘Cantique de Jean Racine’ written by a nineteen year old Fauré. I was unsure whether this was a good fit in this programme but it was sung so beautifully it didn’t matter. The first half of the concert concluded with Arvo Pärt’s ‘The Beatitudes’. There was confident attack of some tricky entries and some difficult dissonant harmonies were well tuned although after half an hour of singing the pitch maybe dropped a bit in some unaccompanied sections. The piece built to a splendid climax demonstrating what has been described as the Levens Choir ‘Wall of Sound.’

The second half of the concert was devoted to Duruflé’s Requiem. The organ part was beautifully played by Ian Pattinson, using the full potential of the fine instrument with beautifully judged registrations. The choir was seemingly caught off guard a little after the short introduction but the music then flowed well, with nice legato phrasing of the plainsong melodies. There was real excitement in the layers of sound in the Kyrie, perfect unison singing then some full-blooded intensity in the Domine. We were also treated to Rebecca Chandler’s rich mezzo tone in the Pie Jesu. She was equally at home throughout her range and her pianissimo singing at the end was breathtaking. The last few movements were all beautifully sung, finishing with a quiet fervour, a long held last note and quite a long silence before it felt right to applaud.It was fitting that the concert was dedicated to the memory of Margaret Jones, a stalwart of the choir since its inception in 1975. Do I have any criticisms? Maybe some consonants were lost in that acoustic, and the men, particularly the tenors, were sometimes a little underpowered with one or two voices being a little dominant to try and make up for that. A few more men needed please! But bravo Levens Choir, and conductor Gawain Glenton whose clear and unfussy direction kept everything on track and plainly inspired the choir to give of their best. More like this please!

Christmas Concert - Windermere

Carver Church was the venue for a heart-warming afternoon of Christmas Carols presented by Levens Choir under the expert direction of Gawain Glenton. The programme held delights in abundance, from old favourites such as The Coventry Carol and Past three o’clock, C20th English composers including Herbert Howells, William Walton and Elizabeth Poston, to contemporary British composers Cecilia McDowall, and Joanna Forbes L’Estrange. Works by three American composers Randall Thompson, Morten Lauridsen and Eric Whitacre completed the rich and

Carver Church was the venue for a heart-warming afternoon of Christmas Carols presented by Levens Choir under the expert direction of Gawain Glenton. The programme held delights in abundance, from old favourites such as The Coventry Carol and Past three o’clock, C20th English composers including Herbert Howells, William Walton and Elizabeth Poston, to contemporary British composers Cecilia McDowall, and Joanna Forbes L’Estrange. Works by three American composers Randall Thompson, Morten Lauridsen and Eric Whitacre completed the rich andsatisfying fare.

The performances were so thoroughly professional it would be easy to overlook the meticulous preparation and vocal skills that lie behind the delivery, unaccompanied throughout and often in more than 4-parts. Levens Choir are fortunate indeed to have fine voices in all parts that facilitate this. Gawain Glenton never let the direction flag, coaxing lovely pianissimos and rumbustious fortissimos when required, and delivering excellent ensemble and much expressive detail throughout – and a rousing finale!

I enjoyed it all, but of the works I’d never heard before I particularly liked Forbes L’Estrange’s Advent ‘O’ Carol with its beautiful harmonies floating above the lower voices, and its magical ending, and the attractive syncopation in the opening work, Now may we Singen by Cecilia McDowall. But there were pleasures at every corner: lovely upper voices in Elizabeth Poston’s Jesus Christ the Apple Tree; the rich harmonic freshness of the three works by Herbert Howells; Holst’s Lullay my liking complete with pleasing soprano solos and fine accounts of the modern masterpieces, Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium and Whitacre’s Lux Aurumque.This was indeed the perfect preparation for Christmas, and Carver Church was an excellent space for the occasion. It is warm and comfortable with a good acoustic and it will be a loss when it closes. We can though look forward to hearing Levens Choir there one more time when they celebrate their 50th birthday on Tuesday July 8th 2025.

Christmas Concert - Bolton-le-Sands

Christmas music comes in all shapes and sizes, from supermarket jingles to traditional Victorian carols. It’s such a welcome change when a talented choir gives us something different, a mixture of ancient and modern carols. And that is exactly what the highly talented and well directed Levens Choir gave us this year. In ‘Now may we Singen’ we had an ambitiously selected and beautifully polished programme.

The title piece is by Cecilia McDowall, a delightfully syncopated and sprightly carol combining medieval English words (‘And thus it is forsooth y-wis’) with modern rhythms and chords. The first half gave us Eric Whitacre’s deeply contemplative ‘Lux Aurumque’ and works by Herbert Howells and Peter Warlock. Among my favourites was Howells’s ‘A spotless rose’, with the solo phrases hanging faultlessly over the choral part.

We were also treated to ‘The Angel Gabriel from Heaven came’, arranged by Willcocks, and the extraordinary liquid numinosity of Lauridsen’s ‘O Magnum Mysterium’, meditating on the part played by animals in the Christmas story. In the Coventry Carol, the choir effortlessly negotiated the switches between major and minor which are so thrilling for the audience. The 20th century English revival by Parry, Walton, Holst and Wood, was wonderfully represented: I particularly admired the angular joy of William Walton’s ‘What cheer?’

The Levens Choir sound is distinctive, with very strong ensemble unity, excellent diction, and full-throated passion. In Gawain Glenton this choir has a very distinguished and capable musical director. Together they bring us an original, stimulating selection, a fresh musical perspective on Christmas. Long may they continue!

Mark Chater

Afternoon Concert: My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land

The latest concert from this excellent local choir was a break from their usual Renaissance offerings; English partsongs, from the Victorian period. As the musical director, Gawain Glenton explains, this genre is often dismissed as lightweight but with composers such as Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Holst, the music is anything but, as the concert most ably demonstrated.

The latest concert from this excellent local choir was a break from their usual Renaissance offerings; English partsongs, from the Victorian period. As the musical director, Gawain Glenton explains, this genre is often dismissed as lightweight but with composers such as Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Holst, the music is anything but, as the concert most ably demonstrated.

Beginning with Elgar’s 'My Love Dwelt in a Northern Land’, setting the theme of this music being based in and around Lakeland, the choir gave us warm harmonies with a strong melody from the sopranos and smooth, precise dynamics for a strong opening piece. It was followed by ‘’Weary Wind of the West’, accompanied from without by Storm Ashley - most appropriate! - and the music building to a grand crescendo in the central section.

Vaughan Williams’ short and lively ‘Over Hill and Over Dale’ was a charmingly light contrast and Holst’s ‘Autumn Song’ with its very autumnal, lyrical harmonies and text by Wiliam Morris changed the mood once more.

The less well known local composer Arthur Somervell was next in the programme, with three quite different songs; the poignant ‘Once I was Young’, followed by the melancholy ‘No Longer Mourn’ and the ebullient love song ‘Ah! My Sweet Sweeting’, a delightful love-lilt. A contrasting trio together forming a coherent whole and delivered with aplomb.

Randall Thompson’s ‘Alleluia’ was next, showing off the human voice as a musical instrument. So difficult to sing a piece like this well but achieved with good balance between the sections of the choir and excellent dynamics.

We then switched from English to Latin for three pieces from Charles Villiers Stanford, beginning with Justorum Animae, where the male voices led the choir into a fine crescendo softening into pianissimo towards the end. The Coelos Ascendit was lively and celebratory, sung with real gusto, followed by the Beati quorum, gentle, almost plainsong in places, the choir passing the text from section to section with effortless expertise.

Another local composer, Phillip Cooke, who was in the audience, provided the next three songs; ‘I Stood on a Tower’, from a poem by Tennyson, with close, dissonant harmonies - a very reflective song, very difficult to sing and very well sung. ‘Green’, the next piece, was much lighter with a sparkling top A from the sopranos the highlight. The cycle closed with ‘How Clear, How Lovely’ with text from Housman and gentle harmonies to conclude the trio of songs. The deserved applause was for the composer as well as the choir.

Finally, and far too soon, the concert concluded with Holst’s Nunc Dimittis, appropriate for time and place. Solo offerings from soprano and tenor the highlights and a lovely way to end a lovely afternoon’s choral enjoyment.

Thanks to everyone involved in the organisation at St John’s - incidentally, this lovely old church has really good acoustics for choral music - and, of course, to Gawain, his splendid choir and everyone associated with making the event run smoothly.

Stephen Porter

A Romantic Journey

Levens Choir, with conductor Gawain Glenton, presented their summer concert of unaccompanied choral music at St. Oswald’s Church, Warton, on Sunday 7th July at 3pm. Entitled A Romantic Journey this was a day-trip through a lush Romantic landscape of short choral pieces by the contemporaneous Brahms, Bruckner and Rheinberger, all with sacred texts in either Latin or German.

The programme opened with the choir encircling the audience. A moment of concerted concentration, then Bruckner’s glorious motet Locus Iste – ‘In this place’ – broke the silence. This ‘surround-sound’ effectively drew us into the lovely acoustic space of the church. Quietly repositioned at the front for the remainder of the concert, the choir set off on the day’s journey with Rheinberger’s Morgenlied – Morning Song. This motet musically painted the fading of the stars, the pre-dawn quietness, and nightingales singing before the day truly begins. Lots of chromatic slides tested pitching well; a lovely subito calm contrasted well with the return of the bright, forward sound the choir make, which had a fitting Germanic ring to it. Confident launches of intervals then a lovely hum of sound brought this descriptive piece to a close.

Fest – und Gedenksprüche by Brahms followed, comprising three contrasting motets for double choir – very challenging music to sing. The first, Unsere Väter hofften auf dich, is a solemn piece that ends with intertwining counterpoint: the whole could perhaps have blocked together a little more. Wenn ein starker Gewappneter is a livelier composition, and the word-painting of solidity against tumbling down was nicely evident, though I would have enjoyed a little more roar from the lower parts to counter the predominance of upper voices. The third motet Wo ist ein so herrlich Volk is antiphonal and complex in structure. The injunctions of the text – ‘take care,’ ‘don’t forget ,’ etc. were effective but I felt I was not being given the full value of the tectonic harmonic shifts.

Another motet by Bruckner, Virga Jesse, restored the equilibrium of the choir, and they brought an almost Russian sound to the music, just short of those full harmonic overtones and buzz. Then Hymne by Rheinberger was equally confidently sung with the flexible shape of the music bringing out a really ‘singing’ quality, though perhaps just lacking some roundness. Christus Factus Est, the last motet before the interval, was another delight: the ebb and flow of Bruckner’s clear harmonies giving me some of the warmth I wanted, and the Amen gave me ‘all the feels’.

A darkly rich sound began the Brahms motet Warum ist das Light gegeben, in which the meaning of suffering and death is questioned – lots of ‘whys’. There was slightly less assurance in the next entry, perhaps in anticipation of the exposed section that followed. If there was fear here however, it didn’t show in the difficult vocal interweaving that expresses less dark questioning. The lovely chorale that is the last of the four sections I thought could have been a little calmer and more potent – a still pool after all the fretting.

The second of the Brahms’ motets that comprise Opus 74, O Heiland, reiss die Himmel auf, gives the start to the tenors and basses who gave it a good descriptive stomping movement – ‘rend the heavens, tear down the gates.’ The high falling entry from the sopranos perhaps was not given all the weight it might have carried, ditto the Amens, but what a fine piece we were treated to.

Who cannot love Bruckner’s sumptous Os Justi, with all its suspensions and resolutions! The second iteration of this distinctive element was more potent than the first which slightly gave away the moment by not maintaining the tensions. The almost Gregorian bass sound underpinned it well. I would have enjoyed a teeny bit more Romantic stretching at times. And then his ethereal Ave Maria threaded together evocatively though the entry was marginally ragged, and the sound sometimes lost sustaining power during the long-held notes.

One more touch of Brahms in a short and sweet canonical Benedictus. After so much complex and strenuous singing, the apparent simplicity of this must have seemed something of a relief. Nice flexible interweaving of voices throughout, though the start was a little thin: it needs to sound as if it already exists as it floats into audibility.

The end of day was given to Rheinberger’s Abenlied – ‘Bide with us, for the day will soon be over’ – a six-part little delight full of suspensions and calm shining beauty. Gorgeous.

The concert was a stimulating mix of well-known and less familiar nineteenth-century motets. The lush harmonies of Bruckner resonated with the choir, and their enjoyment was evident, Rheinberger likewise, but the Brahms felt a little more like the challenge that it is. Because so much of the sound was glorious I noticed the occasional specks that weren’t, like just getting initial consonants out of the way in time for vowels dead on a beat – but admittedly hard to do in high, exposed entries. I don’t often complain of bright, forward-placed singing, nor am I here, but I felt that a little more rounding of the sound to create an ensemble warmth, and a bit more rubato at times might have well suited this Romantic music.

If this music is the cream on warm, jammy scones, (splendid fodder for a summer outing), then I’d say that today, if not quite Cornish Clotted, was instead a luscious, fresh single mixed with double, with rich chunks of butter: not half bad! Thank you, Levens Choir, for a delicious, delightful and satisfying concert.

Wendy Randall 10.07.24

Delightfully unforecast, the sun came out in the late afternoon for the Levens Choir concert today.

This ancient large church had an audience filling the nave and a hush fell waiting for what was to come. The tenors and basses silently took their places spaced out on the crossing and then the sopranos and altos quietly lined the sides of the church. Gawain Glenton walked up to his conductor stand with a quiet dignity and softly whistled the pitched notes for the choir. The stage was set.

The programme cover with a monochrome version of Casper David Friedrich’s young man, the Wanderer, with his back to the viewer, contemplating the Sublime mountainous landscape before him was an inspirational connection to the musical programme we were about to enjoy.

Then the first notes came of Bruckner’s reverent piece, Locus Iste. Written for the consecration of a church, this piece was sung a cappella from memory by the choir. Sitting listening in the nave in a cocoon of sound it was a floating ethereal experience to hear music perfectly balanced from all sides and the integrity of the text came across powerfully through the music. I could have been in a Renaissance church, domed in heavenly cerulean blue rather than the high English rafters of St Oswald’s. Gawain Glenton stood completely still as the last echoes of the final chord gradually faded into silence and we all burst into appreciative applause.

This is the quality of Levens Choir that Gawain brings out of this large group. The attention to text and music is more than the sum of its parts. It really was a beautiful experience directed by an artist.

Rheinburger’s Morgenlied was next – a journey of wonder and richness. The stunning harmonies were a joy and the dip to pianissimo from these massed voices was wonderful. Word painting was beautifully felt.

Brahms’s three sacred motets followed. I particularly loved the great bell-like underlying pulse of Wenn Ein Starker Gewappneter – a spiritual comment on earthly stability which falls apart if internal strife pulls it to pieces. A very timeless dilemma.

The programme continued with two more Bruckner pieces in Latin with another Rheinberger in German between. I read the English translation and could follow much of the diction but was not analysing these wonderful pieces now but just suffused in the glorious music.

A sumptuous first half that I wish I could hear all over again; live music is not BBC iPlayer though. But I want to remember the experience and am thus writing my personal review.

There was more “rich full fat cream” (as Gawain delightfully later called it) of this period of mid-nineteenth century German music to come though after the interval break.

The second half started with substantial pieces by Brahms questioning spiritual issues which were a triumph of composition and performance and the pianissimo was memorably held by the silver soprano lines through the tenor and alto lines to the velvety bass line.

More delicious Bruckner and then the short but deeply moving Benedictus of Brahms.

It seemed to me that time was suspended in this concert and it was the final sacred youthfully composed Abendlied by Josef Rheinberger which finished this glorious concert all too soon.

A well-deserved summer break musically for this great choir which under Gawain’s direction goes from strength to strength. I look forward to the Autumn programme but meanwhile am still resonating with the ethereal sounds that St Oswald’s church held today.

Rich musical full fat cream indeed. Thank you so very much.

Gwenda Meredith

Vivaldi Motets

Sunday 28th April, Lancaster Roman Catholic Cathedral

Sunday 28th April, Lancaster Roman Catholic CathedralReview by Don Gillthorpe

In the second outing of a programme celebrating the works of Venetian composer Antonio Vivaldi, on Sunday 28th April 2024, a large, appreciative Lancaster audience was treated to a splendid afternoon of music from Levens Choir, accompanied by South Lakes Baroque. Lancaster Cathedral was the perfect venue for this concert, with its warm, generous acoustic being ideally suited to sacred choral music.

Concerts featuring works predominantly by one composer can sometimes lack variety, but Gawain Glenton’s expert programming — assisted by Vivaldi’s varied styles and textures in the longer works — ensured that this was not the case at all. The choir showed a great deal of versatility, with tone colours matching well with the moods of the contrasting musical material: from vibrant, joyful counterpoint, to solid, full-bodied homophony, and quiet, reflective passages. The unison singing required in the Magnificat (RV610a) is a trickier thing to achieve than it might appear on the page; this was done extremely well. Also in the Magnificat, the fast, fiery Fecit potentiam section was performed with great energy and clarity; everyone clearly enjoyed this part!

Alongside the works by Vivaldi, Antonio Lotti’s iconic Crucifixus à 8 gave the choir an opportunity to perform a capella, as well as giving the orchestra a well-earned rest. Tuning was generally good throughout this, but the sense of blend suffered a little from unmatched vowels, with brighter sounds overpowering more reserved tones. Otherwise, the balance of the choir was generally very good across the whole programme, with only a couple of misjudged moments from enthusiastic basses and sopranos. In particular, the In memoriam section of Beatus vir (RV597) had a beautifully controlled tenor and alto sound.

The choir were accompanied for this programme by an excellent team of local instrumentalists, supported by visiting Baroque music specialists, who also performed instrumental works to balance the programme (Sinfonias in B minor, RV169, and E flat, RV130, as well as the D minor Violin concerto, RV236). The orchestra featured superb oboe playing from Mark Baigent and Geoff Coates, alongside sensitive continuo playing from Philip Turner (theorbo) and Ian Pattinson (organ), but the star of the show was Hungarian violinist Kinga Ujszászi. From her dextrous handling of Vivaldi’s characteristic dance-like runs, to expertly-phrased, sorrowful, slow-moving melodies, Ujszászi’s playing was full of life and character at all times. The decision to have the strings play with Baroque bows worked extremely well, especially with the bite and bounce needed for energetic passages.

Solo movements for all the choral works in this programme were performed by members of the choir, often in small semi-choruses. Occasionally, singers walking to different solo positions interrupted the flow of multi-movement works and, for one soprano semichorus, standing in front of the orchestra seemed to hinder the ensemble a little. Nevertheless, all soloists acquitted themselves admirably, with well-handled melismas and generally well-articulated text. The soprano and violin duet in Beatus vir (Jucundus homo) was particularly good, with lovely interplay, accomplished, classy playing, and a clear, expressive soprano line. At the end of choral items, applause for the soloists garnered well-earned smiles all round as members of the choir proudly acknowledged their colleagues’ success.

Everyone involved in this performance should be very pleased with the outcome. In their biography, Levens Choir describe themselves as ‘an ambitious and exciting ensemble with a fine reputation for versatility and excellence’: this description is entirely justified.Vivaldi Motets

Levens Choir presented its Spring concert on consecutive days in Kendal Parish Church and Lancaster Cathedral. I was privileged to attend the former. All but one piece was composed by Vivaldi. Antonio Vivaldi, a composer of the Italian Baroque, was known as ‘Il prete rosso’ – the Red Priest - due to the fiery colour of his hair. It was often said that he used to slip out into the Sacristy whilst taking Mass when musical ideas popped into his head. Perhaps on other occasions he went into church to seek divine inspiration!

The dry acoustic in the Kendal venue is in contrast to the spacious acoustic of the cathedral. Gawain Glenton, the choir’s conductor, who leads the English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble, spent his early school days in North Lancashire, had assembled an orchestra of Baroque period instruments to accompany the choir.

The Levens Choir opened the concert with Beatus Vir. In the short introductory instrumental section, I was immediately impressed by the fresh sound quality of the string instruments using a non-vibrato technique. I was pleased to see and hear the theorbo. In this piece, like the other two choral compositions, short portions of text are treated by equally short musical movements. There is never time for either the singers or the listener to settle to a lengthy section of music developing an idea. The early bars of the first movement recur on a number of occasions interspersed between subsequent sections. The balance, chording and tuning are always secure in this choir, as was the balance between the choir and the accompanying orchestra, which in itself is not always achieved.

Then followed the first of three instrumental pieces for the strings, the middle one of which was a Violin Concerto superbly played by the orchestra’s leader Kinga Ujszaszi.

Versicle and Response was the first piece after the interval. In the Gloria Patri, I felt that the lengthy soprano section was a little exposed. The second orchestral Sinfonia of the evening contained shades of Winter from the Four Seasons.

The penultimate piece was the only non-Vivaldi music, namely Lotti’s Crucifixus. Unlike all of the other choral works, this is unaccompanied, and is less suited to the dry acoustic. I’m sure that it would have sounded magnificent in the surroundings of the Roman Catholic Cathedral the following day. It builds in layers with many super suspensions. This was effectively sung.

The concert concluded with a setting of the text of the Magnificat. The continual movement of semi-chorus performers was a distraction. It wasn’t as though any beneficial antiphonal effect was gained. However, another well-performed piece brought the evening’s music making to a lively and fitting conclusion.

It is fairly obvious as to why these pieces don’t command the same number of performances as Vivaldi’s very popular Gloria, but we must thank Gawain and Levens Choir for introducing them to us. Thank you to all of the musicians - including the ever-reliable Ian Pattinson with the continuo part on Gawain’s chamber organ - for a very pleasant evening’s entertainment.

European Christmas

A European Christmas – Music spanning the 16th and 21st centuries,

Levens Choir - Sunday 10th December, 2023

The short review of this Christmas concert might say just that Gawain Glenton led with neat but expressive conducting, and Levens Choir sang with a warm homogenous sound throughout, with enjoyment and verve too. But with music spanning four centuries and eight languages, with many uncommon items, there is much to say, to enjoy, to comment on!

Ticket and times-past passport in hand, I arrived at the warm and welcoming Carver church, for a tour of Europe in words and music. The choir began off-stage humming Praetorius’s Est ist ein Ros. Measured and round in sound this drifted to us like winter mist; harmonic and melodic shifts were clear, each part being equally strong, then the choir processed in singing a version by Vulpius, followed by Sandström’s atmospheric remake which ended with a fearsome bright dazzle of a soprano solo.

Oy v Yerusalimi, a traditional Ukrainian carol, arranged by Yatsynnevich, brought us the evocative clangour of Orthodox Church bells, as early bells rang in Jerusalem, ... and Mary walked in the garden, ...carrying her newborn son – ...a bountiful evening. Lovely surges of sound gave the listener the story. Then we were off to Sweden for Jul, Jul, by Nordqvist. To a perfect Christmas snowfall that covers beauty and ugliness alike, add lights and love, and a sound that was as expressive as the music itself. The choir breathed as one, and pitch was held throughout.

A bold solo bass entry kicked off the energetic Riu, riu, chiu, by the Spanish composer Flecha. This is a bucolic allegory, where the riverbank is protected, the ewe lamb defended from the wolf, and the prophecies fulfilled as God and Man become one. The repetitive riu, riu, chiu is the call of the kingfisher, perhaps the storyteller, and an alto soloist gets a spot in the middle.

Gozate virgen sagrada, ‘rejoice, sacred Virgin’, and blessings on the unknown Spanish composer: in this the wide formation of the choir came into its own as soprano and alto rocked the ancient text from side to side – dec. and cant.. Verbum caro factum est – Señor Anon again, here a key change and a swingy punchy rhythm sung with a strong open sound. Remaining in Spain and back to early 16th century composer Flecha, a solo begins No la devemos dormir, which seems to be a conversation between the Virgin’s thoughts,(solo), and we, the world. The choir and soloist made it credible.

Carol of the Bells some years is heard everywhere in ads, shops, concerts and films … but here, this year, a very engaged body of singers with a really good dynamic range, brought us that old Ukrainian soundworld of troikas swooshing over wide snowy space, their sleigh bells ringing, and then, the distant bass church bell is heard – Bom!

A change of sound came with Poulencs Four Motets. Now we are in a Western Europaen cathedral with wonderfully onomatopoeic music -O Magnum Mysterium. The soprano entry was silvery against a sombre gold of the lower parts, and at the end, a gorgeous concord. Then a change of pace with Quem vidistis pastores dicite. A gentle questioning of the shepherds -’what have you seen?’ and then the strength of the proclamation ‘go and tell what you have seen’. Videntes stellam: the choir produced the crystal sound of frosty stars – good writing by Poulenc of course – and a lovely ebb and flow as the Magi duck under the lintel and quietly bring gifts to a Baby. Hodie Christus natus est, was almost Slavic in its crunching sound. What a contrasting but integrated four pieces making a joyous conclusion to the first half.

The sweeping, joyful sound of Sweelinck’s Hodie Christus natus est, from a rearranged choir, began the second half, interweaving the Latin text with high energy and delight. This continued in Les Anges dans nos campagnes, - Traditional French, which we know as Angels from the Realms of Glory, sung with evident enjoyment and excellent fluctuations of dynamics.

Grieg’s Ave Maris Stella followed, in Latin, but with that Nordic sound akin to Ukranian and Georgian music. It must be the snow… Nice suspensions and resolutions in the music. Also in Latin, O Jesu mi dulcissime, by Gabrieli: glorious harmonies and classic Gabrieli swell and release, the antiphonal two-part sound worked with the wide choir format. I could have been in the Basilica of San Marco. Staying in Italy we heard Dormi, dormi , del bambini. I wish I knew who this Anon was as I’d like to thank him. Charming - and full of pathos – Mary knows all that is going to happen to her son.

Well placed was the following Bogoroditsye Dyevo by Rachnininov, a ‘Hail Mary’ in Church Slavonic. Gawain subtly indicated at the start that big barrel sound that all have to find to sing this. Good sustained sound, and the basses were almost Georgian.

The traditional English Wexford Carol next, arranged by Rutter. A solo tenor leads all in, and holds the whole together in a simple telling of a tale. Very moving and well done. Interwoven humming by the choir upheld the solo voice singing Suantraí át Slánaitheora, who had just the right sound for the Irish. Lovely harmonic shifts and ending, in this simple lullaby sung by a mother to her newborn baby.

Praetorius revisited in Joseph Lieber Joseph mein… the text in German and Latin, but that big Deutsch sound… delicious – I close my eyes and I’m in a (cold) kirche - the townspeople sing up and down the streets, heading home. I expect to hear the dolorous racket of German bells at this point …. and I did – but bright and jingling as the choir encored with Carol of the Bells.

It was after the first couple of pieces that I registered that the music was unaccompanied, so full and rich was the sound that there was no lack. The entire programme continued unaccompanied, occasionally punctuated by an apt and well read poem. In brief, a commendable choir singing a meritorious programme of gorgeous music making a thoroughly delightful evening. Thank you all.

Wendy RandallTwo Elizabethans - choral music by Britten & Byrd

The latest performance by the Levens Choir under the direction of Gawain Glenton featured music by two composers separated by four centuries, William Byrd (1543-1623) and Benjamin Britten (1913-1976). The entirely unaccompanied concert in the acoustically-splendid St Oswald’s Church, Warton, was very well attended by an appreciative audience who were given a virtuoso display of choral music of the highest quality.

The latest performance by the Levens Choir under the direction of Gawain Glenton featured music by two composers separated by four centuries, William Byrd (1543-1623) and Benjamin Britten (1913-1976). The entirely unaccompanied concert in the acoustically-splendid St Oswald’s Church, Warton, was very well attended by an appreciative audience who were given a virtuoso display of choral music of the highest quality.

The evening began with Byrd’s 1590 anthem ‘Sing Joyfully’, a text drawn from Psalm 81; a bright, cheerful start with clear notes and harmonies and lovely dynamics. We then moved on to the first two parts of Byrd’s Mass for Four Voices, the Kyrie and Gloria - a more measured pace with strong base lines in the Gloria underpinning the harmonies and the alto section shown off to good advantage in this classic Tudor Renaissance piece.

Glenton cleverly split the Mass here, interposing Britten’s Advance Democracy, giving a huge contrast to the previous works. This dramatic warning of the gathering war clouds in Europe (written in 1938) uses melismatic sections laid over abrupt, jackboot-like utterances from the other voices and switches from major to minor keys bringing a feeling of threat and danger.

We then went back to Byrd’s Mass for the Credo and the perfect counterpoint to the horror of war. The sharp harmonies were particularly well shown by the sopranos in this expression of the spirit of faith with the tenors lending fulsome support.

The first half concluded with a rendering of Britten’s Five Flower Songs (op 47 of 1950). This song cycle, with elements of Elgar and Parry, provided the choir with a real challenge to which they rose magnificently. The contrast between the light touch required for To Daffodils to the almost menacing, slightly discordant harmonies of Marsh Flowers and the lyrical The Evening Primrose were handled with aplomb.

The second half began with Britten’s Deus in Adjutorium, his setting of Psalm 70 written in 1944-5 for a radio play. A rousing opening piece, delivered crisply and with precision. The sopranos were particularly prominent and the central canon was expertly performed.

Then came perhaps the best-known work of the evening, Byrd’s gorgeous Ave Verum Corpus. He wrote this in about 1605 but the original dates from the 13th century. The rich harmonies rang through the delightful acoustics of St Oswald’s with great balance and clarity. A quite superb rendition.

Then came, for your reviewer, the pièce de résistance of the evening; Britten’s A Hymn to the Virgin. Written when the composer was only 16, this minor masterpiece is a dialogue between two sections of the choir, one singing in Latin, the other in English. Glenton split the singers to opposite ends of the church; simple but magically effective. Absolutely divine.

The concluding two parts of the Mass for Four Voices then followed, the Sanctus and Agnus Dei, with the full choir together again and in full voice. Despite the relative small number of male voices in the choir the balance was perfect, well shown in these pieces. The finale of the Agnus was quite beautiful.

Two short Byrd compositions followed; Even from the Depth, from Psalm 130, written about 1558, and Look Down O Lord, from 1614 - the latter from a collection entitled ‘In the teares or lamentacions of a sorrowfull soule’. Delightful cameos perhaps reflecting Byrd’s more introspective nature.

Which set us up for the grand finale - Britten’s Hymn to St. Cecilia, op. 27, based on Auden’s poem. The choir supported the excellent soloists (Lucy Crispin, Sally Dickens, Rose Jones, John Ward and Charlie Lewis) in this tribute to the patron saint of musicians (Britten was born on St. Cecilia’s day) to bring the wonderful evening to a rousing close, reflected in long and appreciative applause.

Steve Porter, 10 July 2023

Bach & Pärt - the power of the spirit

The programme was framed by two great motets by J.S. Bach, interspersed with the music of some of Bach’s older relatives and of Arvo Pärt and Henryk Górecki. This was an unusual mix which allowed the enthusiastic audience to enjoy the composers’ contrasting personal pursuits for spiritual truth in music. The Victoria Hall in Grange might not seem the obvious choice for a programme of this sort, but the building and the choir are a perfect match. It is an intimate space which gives a fantastic, honest platform for a choir of this size, and helped the audience to feel immersed in the choir’s clear, warm sound.

To name a few of the individual pieces: Komm, Jesu, komm is a virtuosic motet for two choirs of four voices with long weaving lines, which is huge favourite of solo voice ensembles. The music was tackled with a sensitivity to the interplay of the voices and with Lutheran fervour by the choir, and the music flowed with momentum towards its final chorale. This felt like fun chamber music. Pärt’s Deer’s Cry which followed, a prayer for protection, has a poise and warm, contemplative feel which is given power by its repeated phrases, the silences in the music, and soaring soprano lines. It was beautifully paced.Some delightful solo playing on a Walter Chinaglia chamber organ by Christopher Stokes split each half of the concert in two. It is rare indeed to hear an audible laugh whilst listening to solo organ music. J.C. Bach’s Fugue on B.A.C.H. delighted the audience, providing a charming sorbet in amongst the more austere choral settings. The Pärt and Górecki pieces were sung with great impact and control, with rousing crescendos. The mesmeric and sustained fortes in the Pärt Nunc Dimittis and the imploring repeated cries of ‘Maria!’ in the Górecki Totus Tuus were thrilling. This is monumental music which inspires goosebumps.

Levens Choir, founded fifty years ago by Kendal’s choral mover and shaker, Ian Jones, is in safe hands, with its excellent organisation, talented singers and the inspiring new(ish) conductor Gawain Glenton at the helm. His deep understanding of the music he chooses, and his clear and encouraging direction produce excellent results. There are quality singers in each section which help all to raise their games, and tackle virtuoso repertoire. There was some excellent work from the soprano soloists, from the smaller groups in the Bach motets, sonorous low notes from the basses which underpinned the Eastern European repertoire in particular, and virtuosic singing from the inner parts which are given music of great interest. The result is homogeneous and sonorous and the audience was drawn in by the sincerity and depth of the music, sung with serious attention to detail, care with the language and committed communication.The evening’s programme ended with the tender final ‘gute Nacht’ of Jesu, meine Freude. A joyous encore of Pärt’s Bogoróditse Djévo left the audience on a high.

Gawain Glenton’s programme note and insightful chats in between pieces invited the audience to enjoy and feel involved in the music and music making. That we did. Bravo to all. What a joy to be treated to live music again.

Nicholas Hurndall Smith

Bach & Pärt - the power of the spirit

Levens Choir under their conductor, Gawain Glenton, are to be congratulated on performing an ambitious and exciting programme with such aplomb. They delighted the audience at St George’s Church, Kendal, with their dynamic and musical interpretations of pieces by Bach and Pärt, the former sensitively accompanied by Manchester Cathedral organist Christopher Stokes, on a 2009 Walter Chinaglia baroque organ.

The programme was book ended by two Bach motets. Komm, Jesu, Komm gave us a foretaste of the quality of this choir with its precisely articulated opening contrasted with some fine legato singing. The choir was at its best, though in the final Jesu Meine Freude, a cantata which demands many different styles of singing. All were tackled with conviction and confidence; stately chorales contrasting with the complexities of the fugue.

Christopher Stokes demonstrated the colours of the organ with movements from JS Bach’s Pastorale and a delightfully showy Fugue on B.A.C.H. by J C Bach.

The pieces by Arvo Pärt and Henryk Górecki pointed us to a very different approach to religious music, reflecting the more contemplative and spiritual style of the Eastern Orthodox Church. These pieces demand a sonorous tone and pitch perfect tuning to allow the harmonics to ring out. This was achieved beautifully in The Deer’s Cry with the lower parts providing a wonderfully rich and mellow base over which the sopranos could soar. The Górecki Totus Tuus was full of drama. The ensemble at full throttle was spine tingling, as was the control in the final repetitions at the end which maintained pitch and tone as they faded away.

We were treated to an encore of the party piece of the evening, Bogoroditse Djevo, by Pärt. This was impressively sung in Church Slavonic. Something of a tongue twister, it was full of character and verve, bringing to an end an excellent concert by this ever improving choir.

Anne Pater

Christmas past, Christmas present

LEVENS CHOIR CHRISTMAS CONCERT 13TH DECEMBER 2022

Under the title Christmas past, Christmas present, Levens choir presented its Christmas 2022 programme to a large and appreciative audience gathered in Carver Church, Windermere. And it was an early Christmas present to the audience with examples of British music ranging from the 15th to 21st centuries.

All of the music was unaccompanied, so there was nowhere to hide for the choristers. Not that they needed to. The choir was confident, in good heart and voice. They were well prepared by their relatively recent new director Gawain Glenton. One of his main musical outlets is with the English Cornett & Sackbut Ensemble, but he is clearly equally at home in front of a choir. His enthusiasm is infectious.

The concert opened with MacMillan’s O radiant dawn. The declamatory impact was instant, assisted by the choir being spread out along the length of the church. The audience were closer to the performers, and therefore we felt more engaged. This piece was followed by Byrd’s Puer natus est nobis. Here, the clear lines of the vocal parts were impressive. Ravenscroft’s Remember O Thou man was treated particularly sensitively in the quieter verses. The choir was given just one note before the start of all of the pieces, and I wasn’t convinced by the first chord in this piece. Otherwise, they were immaculate.

The programme was interspersed with readings given by Anne Preston. She complemented the music content, commanding the atmosphere, and with humour at appropriate times throughout the evening.

Long, long ago by Herbert Howells started the next group. The choir was confident, and the final chord was exquisite. Two contrasting pieces by Parry - I sing the Birth and Welcome Yule – demonstrated the choir’s versatility. I hadn’t heard, sung (or to be honest knew the composers of the next pair of pieces) – Bernard Hughes’ The Linden Tree and Richard Pygott’s Quid petys O fili from opposite ends of the C16th/C21st spectrum, the latter contained two-part echoes of the very early Renaissance period.

The first half concluded with Good-will to men by Dobrinka Tabnakova, Bulgarian born, but musically educated in Britain.

After the interval, we heard a different aspect to Sir Arthur Sullivan’s compositions, All this night bright angels sing. Here, the chording was excellent.

Further contrast in a programme of repertoire spanning the centuries from the 1500s to the 2000s was Peter Warlock’s lovely Bethlehem Down and Christopher Tye’s A sound of Angels.

John Tavener’s The Lamb is a particular favourite of mine. It looks innocuous but is not easy to sing, and the choir captured its beauty.

Very few choral programmes these days escape at least one piece by Bob Chilcott. His rhythmical style in Pilgrim Jesus is exciting. Another modern offering, this time Stopford’s Lully, Lulla, Lullay had a real lilting quality.

Cecilia McDowall’s Of a Rose ended the evening’s music, sending us home in a jolly festive frame of mind

The conductor thanked the audience for its support and invited singers to join the choir. In turn, I thank the choir and Gawain for the hard work and getting the Christmas music season off to a very good start. He is a most welcome addition to the South Lakeland music scene.

Robert Talbot 15 xii 22‘1922’

1922 was the Orwellianesque title of this year’s Levens Choir Summer Concert. In the year of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee, we were invited to reassess L. P. Hartley’s declaration that ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there’ through music and words written shortly before and after her birth. At one end of the continuum, the ‘spiritually aware’ music of the atheistic Vaughan Williams and the intensely personal ‘conversation with God’ of Frank Martin, and at the other, Adrian Self’s setting of Dover Beach, a reflection on the uncertainties of faith in the face of ‘scientific enlightenment’.

By way of contextualisation, readings from Joyce, Woolf, Williams and Eliot reinforced the point that the decade after the Great War marked a seismic re-alignment of the social, political and religious mores of Victorian Britain. Whether or not intentionally, Orwell’s prophetic vision of the consequences of totalitarianism were evoked both by the title and reflecting on Putin’s imperialist invasion of Ukraine. Far from being a different country, the past seems very much a homeland to those that care to look around them. To quote Willy McBride, ‘it’s all happened again and again and again and again...’

Together with Holst’s Nunc Dimittis, the two masses evoke the Roman Catholic tradition through their Latin text and use of double choir polyphony. In the case of the Vaughan Williams and Holst, further textural contrast is provided by ‘verse’ sections. All four pieces are intended to be performed a capella - a feat only to be attempted by the most competent and confident of choirs.

1922 is the second concert to be conducted by Levens’ new Musical Director, Gawain Glenton, a practitioner well-versed in the complex demands of polyphonic counterpoint. His direction is clear and the choir has been well-trained to sing with a sense of line and attention to detail - the tell-tale signs of a first rate ensemble. This was evident from the opening of the Vaughan Williams Mass and the well-paced and beautifully shaped imitative entries of the nine-fold Kyrie eleison which also featured the first of two excellent solo quartets. The antiphony of the Gloria and Credo were well balanced - this is a choir with strength and depth across all voice parts - though the dramatic interplay between the two tutti and soli choirs could have been further enhanced by separation, as would be the case in a liturgical context. The Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei demonstrated the choir’s ability to embrace rapid changes in texture, dynamic and metre and the final, poignant plea for peace of the Agnus Dei in which the altos recall the opening theme of the Kyrie, was particularly moving.

Holst’s Nunc Dimittis with its progressive rhythmic and dynamic crescendos, stands as an unusual setting in the canon of sacred music. The layered entries of the opening were carefully shaped, the solo sections assured, and the high tessitura of the top sopranos in the declamatory ending, confident and well-sustained.

It is difficult for an audience to appreciate and a choir to grow into a piece on one performance. Self’s evocative setting required more observance of hairpins and a greater regard for textural balance fully to realise his intentions. The harmonic language is challenging and would have taken some learning, but the choir now needs to see beyond the notation to the music.

The performance of Martin’s Mass contained many beautiful moments and the deeply moving Agnus Dei was sensitively managed. Few amateur choirs can produce bass bottom D drones and soprano top B naturals and yet Levens managed this with consummate ease. Although there was a clear sense of relief in the faces of the singers at the end of the Sanctus, having navigated its 5/8 metre and contrapuntal textures, the overall performance was convincing and assured and provided a fitting climax to this ambitious and thought-provoking programme.

Duncan Lloyd

The Glories of Venice - Monteverdi and his world

The Levens Choir gave its first two concerts under its new music director Gawain Glenton, accompanied by the English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble. Gawain is an internationally-renowned virtuoso of renaissance Venetian music and his choice of music reflected his expertise. His focus for these concerts was the work of Claudio Monteverdi.

The opening piece, Domine ad adiuvandum, got things off to a cracking start - a veritable fanfare of voices and instruments with great support from the soloists, one of whom was drafted in at very short notice. The choir was in perfect synchronisation and note-perfect from the off. This piece, part of Monteverdi’s best-known work, the Vespers of 1610, had choir and ensemble in clear understanding and set the tone for the evening.

Then followed Alessandro Grandi’s Nisi Dominus, sung by the soloists with the sackbuts providing fine accompaniment and the choir supporting - a showcase for the expertise of the professional musicians. Monteverdi’s Domine ne in furore gave the choir the chance to demonstrate its skills, providing a lovely round, rich sound, helped by the sympathetic acoustics.

Other highlights included Franzoni’s Sancta Maria, where the female voices complemented the bass notes of the sackbuts beautifully; Gabrieli’s Beata es virgo, which gave the ensemble a vehicle to demonstrate their prowess on these rarely-heard early instruments; and the conclusion to the first half of the concert, Monteverdi’s Beatus vir, which saw the choir pass the text from section to section flawlessly.

Your reviewer was reminded more than once of the Hilliard Ensemble with Jan Gabarek - the way the voices and instruments complemented each other was very similar. High praise indeed.

And so to the second half, where the choir gave us a rich, deep, resonant sound in Monteverdi’s Cantate Domino, followed by his Adoramus te, Christe, a much gentler piece with lovely clear lines from the altos. The Audi coelum featured the tenor soloists in counterpoint from opposite sides of the church. Grillo’s Sonata prima had all seven musicians, with Gawain prominent on cornett, playing with a remarkable agility and lightness of touch.

Then back to Monteverdi to conclude the concert: his Ave Maria Stella showed his characteristic variations on a simple tune and the final Amen was glorious; and finally, the Magnificat primo, which really was magnificent and which featured a fine duet from basses from the choir, drew things to a rousing conclusion. The applause at the end was long, warm and fully deserved.

Overall: the soloists were clearly very familiar with the works, performed well and linked with the choir seamlessly; the ensemble were absolute masters of their craft and played with obvious brio; and the programme was interesting and varied, providing a perfect introduction to the genre for the uninitiated.

And the choir was magnificent. The energy in the choir throughout was obvious - many of the singers had huge smiles - and the commentary from Gawain provided background information which added to the enjoyment greatly.

After nearly 50 years under its founder, Ian Jones, who built the choir’s deserved reputation, the future with Gawain Glenton at the helm looks every bit as promising. Bravo.

SP11 April 22

The Glories of Venice - Monteverdi and his world

Venice was at the heart of European trade in the 16th and 17th centuries and, coupled with political and religious tolerance, created the conditions for music publication and performance to flourish there. This was the historical background to this evening’s concert which so richly brought to life the music of that time and place.

Covid has been a scourge for choirs and continues to make public performances problematic, with last minute call-offs. That Levens Choir were able to perform to their customary high standard is a tribute to all those taking part, and is a relief to concert-goers, grateful that ‘live music’ is beginning to flourish again. Supported by the English Cornett and Sackbut Ensemble (ECSE) and vocal soloists, and under new choir director Gawain Glenton, we heard some accomplished presentations of an ambitious programme of works by Claudio Monteverdi, Alessandro Grandi and Giovanni Gabrieli, amongst others.

Levens Choir’s ability to remain sure-footed and well-blended even when in eight or ten separate parts is commendable, a testament to their depth of resources, though I was sorry not to see the youngsters that have graced the choir in the recent past. The presence of ECSE and a chamber organ brought a pleasing variety of sound colour to proceedings, the sackbuts conveying a rich sonority whenever they played. The short prayer by Amante Franzoni ‘Holy Mary pray for us’ sung by the sopranos and accompanied by sackbuts was beautifully executed. Performances in thefirst half though, I felt, were somewhat understated, and I was beginning to think that the Lancaster Priory acoustic was affecting the impact of the choir, until the final item before the interval, Monteverdi’s ‘Beatus Vir’, which brought the first half to a rousing conclusion.

This was a foretaste of what followed in a second half full of variety, caution thrown to the wind. ‘Aude Coelum’ from Monteverdi’s Vespers, to which the singing of the two tenor soloists Ian Honeyman and James Savage-Hanford brought an admirable dramatic intensity, was particularly full of energy. The choir resting, ECSE almost transported us to St Mark’s Square. The verses of the hymn ‘Ave Maris Stella’, each framed by ECSE, were serenely presented, with delightful solo contributions not least from sopranos Fiona Weakley and Rachel Little. Monteverdi’s ‘Magnificato Primo’ brought the concert to an energetic conclusion, with fine rhythmic precision and dynamic variation. The tenor soloists’ exchange was again splendid.

John Hiley, 11.4.22For St Cecilia: Finzi, Britten, Purcell, Howells

Ian Jones, the founder and conductor of the choir, was performing at his final concert. That is a great pity, but it is better to retire whilst still at the top of your game. He had chosen a number of his favourite pieces. It was Ian who introduced me to the music of Finzi many years ago, and there is a lasting impression.

The concert opened with that great C20th English choral composer Herbert Howells' Hymn to St. Cecilia. Immediately we were engaged by a rousing unison sound in the first verse.

Daughter of another great English composer Gustav, Imogen Holst's unaccompanied A Hymn to Christ was given a firm foundation by the bass line. Coincidentally, this piece was sung the following day on BBC Radio 3's Choral Evensong live from Truro Cathedral.

O Clap Your Hands together all ye people, is a setting of Psalm 47 composed in eight parts by Orlando Gibbons. Like Laudibus in Sanctis by William Byrd later in the programme, could have done with a more sympathetic acoustic, and the execution was closer to madrigal style than English sacred choral music.

Tenor soloist James Marczak, ably accompanied by Andy Plowman, gave a lyrical performance of a beautiful song by Howells, King David.

In Valiant-for-Truth, music by Vaughan Williams, the part singing was secure, and here again, the basses were the choirs secret strength. The section including 'Death, where is thy sting?' was powerful.

Britten's Hymn to St. Cecilia contains an imitative section, and this was particularly effective.

The only non-British piece was Chant donné by the French composer Duruflé. This is a solo organ piece with sumptuous harmonies played Andy Plowman. It was a very sensitive performance. Andy made the best of a very basic electronic instrument.

Levens Choir commissioned Adrian Self to set Three Songs for Christine, words written by a choir member who had died two years ago. Adrian always writes effective and sensitive music. I particularly enjoyed his 'Thoughts of a Corncrake on the RSPB Reserve, Coll'. The humour was well captured in his music - and the choir appeared to enjoy themselves.

The concert concluded with Parry's My Soul There is a Country in which the chording at the outset took a little time to settle, and some entries lacked unanimity, but Finzi's For St. Cecilia brought the concert to a fitting climax. I must confess that I had never heard this piece before, but the choir sold it to me. After a regal keyboard introduction, the choir took us on a harmonic adventure.

Overall, this was an enterprising and challenging programme, and Levens Choir certainly assisted our celebration of S. Cecilia.

Crosby Ravensworth - Music in Quiet Places

Starry Music

%20(905x1280).jpg)

A rare musical treat was unveiled for the audience at the Levens choir Christmas concert. Amongst carols, a string quintet and some seasonal music from Finzi, the highlight of the evening was the Missa Sancti Christophori by Antonio Lotti, a Baroque composer best-known for his 8-part setting of the ‘Crucifixus’ from this work. The Levens choir took on the challenge of this substantial work with spirit and energy, and were ably and sensitively accompanied by the string ensemble (led proficiently by Pam Redman) and Andy Plowman on continuo. The Music Director, Ian Jones, drew out the very best from the choir, with precise articulation and the contrapuntal passages neatly interwoven throughout. The voices were well balanced, with solo parts competently covered by choir members, and careful shaping of phrases ensured variety and interest, with a sustained and full sound worthy of a larger choir. The Crucifixus flowed beautifully despite some initial hesitancy at the start, and all 8 parts moved as one to give a delightfully rich and textured wash of sound. The choir did full justice to this magnificent yet challenging work, and should be commended for their performance.

After some well-chosen carols (including the Stable Carol written by choir member Robert Duffield, a gentle and lyrical piece with some pleasingly complex moments), the string quintet performed the Bax ‘Lyrical Interlude’. This is a very pleasant yet little known work, which reflected Bax’s interest in Celtic culture. The quintet played with cohesion and sensitivity, with players supporting each other to create a perfect balance. There was skilled and controlled playing throughout, with some beautiful warmth of tone in particular from the violas.The concert closed with Finzi’s ‘In Terra Pax’, which intersperses the poem ‘Noel: Christmas Eve 1913’ with St Luke’s account of the angels’ visit to the shepherds. The choir brought across the solemnity of the occasion well, with soloists Edwin Reynolds and Rebecca Chandler taking the parts of the poet and the angel confidently yet with gentleness and delicacy of tone. There was a triumphant and joyful climax, with the choir skilfully passing passages back and forth to create a cacophony of pealing church bells to proclaim the birth of Christ. This was an exuberant performance, a perfect end to a most enjoyable evening.

Veronica Dunne